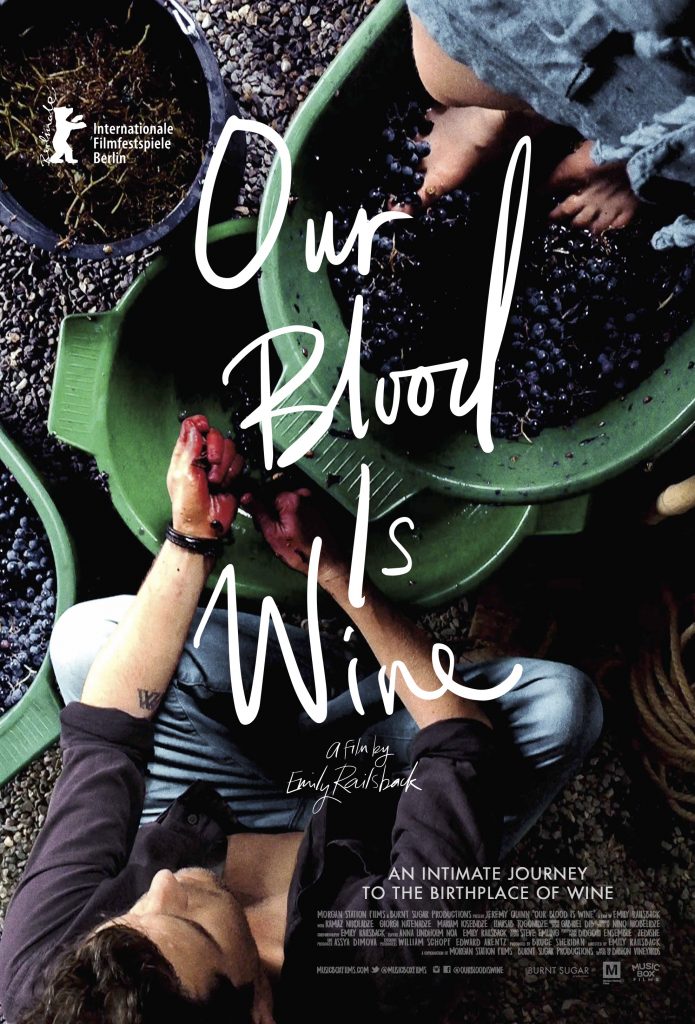

In the country of Georgia, winemaking is a tradition that goes to the very core of the human experience. It’s a story that has been told beautifully in books like Alice Feiring’s For The Love Of Wine, and now it’s the subject of a feature length film from filmmaker Emily Railsback and Music Box Films.

Shot primarily on iPhone for maximum intimacy, Our Blood Is Wine follows the journal of American sommelier Jeremy Quinn, who moved to Tbilisi in 2014 to work as a sommelier and consultant for the country’s ancient, newly-remerging wine scene. Railsback follows Quinn on a journey across the country in search of ancient grape varieties, meeting some of Georgia’s most esteemed winemakers along the way, and encountering the country’s next generation of leading wine minds, many of whom happen to be women. It’s a riveting, beautifully shot film, complete with original music by Nino Arobelidze and Gabriel Dib.

Our Blood Is Wine debuted at the prestigious Berlinale International Film Festival, and will be screening across North America in the months and weeks to come, including March 13th at Cinema 21 in Portland, Oregon; March 14th at the Avalon Theater in Washington, DC; and March 16th at the Music Box Theater in Chicago, in conjunction with the 2018 Third Coast Soif natural wine fair.

To learn more about Our Blood Is Wine, I spoke digitally with filmmaker Emily Railsback fresh off her film’s debut in Berlin.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Hey Emily, thanks for speaking with Sprudge Wine. As an introduction, can you share a bit of background with me on your work as a filmmaker?

Emily Railsback: My background is in theatre and visual arts, specifically photography, graphic design, and painting. I came to filmmaking, because I wanted my photographs to tell more complex stories about social injustices. Documentary was my interest when I applied for film school, but funny enough I didn’t take any classes in it. I fell in love with narrative filmmaking, and made seven short films from 2012 to 2014. I was eager to make a feature film, and writing a script would take too long. (For the record, I’ve been working on a script for the past year, which will soon be ready.) During film school I had worked with Jeremy at a wine bar. He was drawn to the aspects of wine that draw all humans together and wanted to learn more about wine’s origins. He took a sommelier job in Tbilisi, Georgia, and I went to visit him in 2014. We were traveling through mountain villages and he mentioned that Georgia is home to over 500 native grape varieties, and there was no way to taste them all unless you visited the families across the country. He had a crazy dream to walk across the entire country on foot, and taste all the wines. I thought the idea was absolutely crazy, but realized it might actually make a good film. I told him I would find us the funding, and be back to make the movie. He of course didn’t believe that it would happen.

I decided to shoot the movie on the iPhone 6, because it was all I could afford at the time. Once we got funding, I realized I could choose a different camera, but I still like the intimacy that an iPhone gives to the viewer. The camera never got in the way between me and the Georgian families. Had I used a Canon, it might have. We weren’t sure how the final film would turn out, because we didn’t have a script. I guess you could say I’m a bit of a guerrilla filmmaker who is drawn to capturing reality in a cinema verite sort of way.

What drew you to Georgia? Why make a film about Georgian wine?

Jeremy was originally drawn to Georgia because of the wine, but we both fell in love with the country because of its people. There are many wine movies out there, but we wanted to tell a human story about a people whose connection to wine became their identity. That was something we hadn’t seen before. We are currently working to expand this idea to other wine cultures on the fringe of the wine scene. Our next stop is Japan.

How long was the shoot? How long were you there in Georgia?

We lived in Georgia for five months, and accrued 170 hours of footage. And thus the editing process took two years. There was too much footage to work with, and we could’ve made many different types of films. One edit was more focused on the production of winemaking, but that didn’t feel poetic or interesting. We eventually found the story within the footage. We decided to use the elements of the iPhone that make the story unique. The viewer should feel they are coming along with us. They are capturing the feel of Georgia; the singing, the food, the wine, the qvevri, the religion, the families.

The first words in the film are “Do you want cheese bread?”—can you talk more about the huge role food plays in Georgian culture?

Food was a part of everything. It was not our intention to film food, but every time we visited a family they offered us food. It crept into the frame. Sometimes we were offered khachapuri (cheese bread) by three different families in one day. Their cheese is salty, and every region has a slightly different way of making this classic Georgian dish. Needless to say, we both got a little round while living there.

Talk to us about Mariam Iosebidze, the first female Georgian winemaker to export her wines, or new winemaker Ketevan Bershvili, both profiled in the film — are these women winemakers an anomaly? Or the first wave of a new trend for women winemakers in Georgia?

When we were filming in 2015 there were only two wines we knew of made by women. Mariam’s Tavkvari wine, and a chinuri made by Marina Kurtanidze. In both cases they were encouraged to start making wine by the men in their lives. It was actually Marina that began as the first woman winemaker, who was encouraged by her husband Iago of Iago’s Wines which is quite well-known in the States. Iago had visited wine fairs and saw that women made wine in Italy, and thought Georgian women should also start making wine. This was actually quite a progressive idea for Georgia, which has been a patriarchal society for years. However, the country has a deep respect for women, even if many of them keep traditional roles. Georgia loves their King Tamar (a woman king) who ruled Georgia at the height of its empire. Even their language doesn’t indicate gender words.

Mariam Iosebidze was the first woman to export her wines from the 2014 vintage. It was her uncle who gave her a qvevri, and all of the men winemakers in our film who have helped her along the way. There is really a sense that everyone should make wine. It’s contagious. In 2015, Mariam’s second vintage, we decided to make wine by happenstance. That same year Ketevan Berishvili also began to make wine with her father. Keto Ninidze started making her own wine in Samegrelo with the support from her husband’s already developed winery. That same year our friends Luarsab (the ethnographer) and Levan (a filmmaker) started making wine. I really believe making wine is so deeply engrained in their culture, that it feels natural that women make wine. They have always helped with the process, and also have a great knowledge of winemaking and work in the vineyards. I can now think of at least 10 women winemakers, maybe more. The number continues to grow.

What’s your personal favorite Georgian wine?

Part of the reason Jeremy and I didn’t talk about specific tastes and wines in the movie, is because we both feel that once you label a wine as a favorite it starts to promote that grape varietal. People identify with that story and grape varietal, and homogenization begins to happen as a result. We both believe in preserving taste, and that means preserving all the species and a variety of tastes. It’s important for us to continue drinking and tasting things that might at first be off-putting. Our favorite wines come from Western Georgia, where there is a little higher altitude, higher acidity and more prominent minerality in the grapes.

What are some other documentaries that inspired you in making this film?

All documentaries by Werner Herzog. There were many times when editing that I didn’t know how to make a transition between one topic and the next. I’d watch his films, and be inspired by the way he uses film as an ellipsis. It’s poetic, and his transitions are always interesting. Sometimes he’ll follow a new character that doesn’t necessarily relate to the overall story. Once I finished the film I came across “Mur Mur” by Agnes Varda. Watching this film made me realize that this is the approach I was hoping for with my film. Seeing her film after mine was a way to identify the style I was feeling but didn’t know how to explain. It’s interesting though.. both of these filmmakers work between both narrative and documentary formats. I think I relate to blurring the lines in storytelling.

I really appreciate Ketevan’s point in the film about keeping the enterprise in Georgia small—but is the goal to avoid scale altogether? Or to scale authentically?

I believe the key in Georgian winemaking is to make interesting wines with their authentic approach. We briefly touched on this in one line of narration: Georgia’s main economy is based on wine. But only 1% of that wine being sold is made in qvevri, in their traditional method. We think the best approach is to stay authentic, but naturally that means you can’t produce as much. Ramaz’s dialogue rings true, that each qvevri needs different care. You can not mechanize this approach with the qvevri. It takes time and attention.

To that end, is there any fear that increased attention on Georgian wine thanks (in part) to your film may place too much demand on these winemakers?

There is already too much of a demand on these winemakers. However, we believe it is a good thing. Because other people are returning to their villages and making wine in a similar method. There is a problem of village life dying out all around the globe. It is our hope that our movie will help inspire young people to work the land and help create a diverse ecosystem, supporting a variety of tastes.

You wore many hats in making this film—director, operating camera, editing—and so does the finished product feel to you like a personal statement?

Ha! Yes. This film feels like my baby. I was actually a little depressed once it was over. Can you have post-partum for a film? For three years I had been working on this single project. At certain times in the edit I was having to work a full time job, while also being the full time editor. When I finished the film I began to see a thread in all of my work that I hadn’t connected before, the environment sets a tone for everything. There is a terroir to my films. Each film has a specific feel, which comes from place.

Thank you.

For more information and news on upcoming screenings, visit the official website for Our Blood Is Wine.

Photos courtesy of Music Box Films.