“Are you aware of The Fellowship of Friends?”

I am sitting in the tasting room of Renaissance Winery, located in the rural Yuba County hamlet of Oregon House, California. We’re an hour or so north of Sacramento, and just a few miles east of the vast, sprawling Tahoe National Forest. Here in the picturesque Sierra Foothills there’s a 1,300-acre property known as Apollo, owned by a religious group called The Fellowship of Friends—referred to by members as simply “The Fellowship”—founded several decades ago by a spiritual teacher named Robert Earl Burton.

According to his official website, Robert Earl Burton founded The Fellowship on New Year’s Day 1970 after studying with a theater director named Alexander Francis Horn, himself a follower of the teachings of Peter Ouspensky and George Gurdjieff. These teachings, known as the “Fourth Way,” focus on sprawling concepts like “self-remembering” and “presence,” with the goal being “to increase consciousness by a direct effort to be present within this moment.” Burton still lives on his Apollo compound today with 500+ active followers nearby; he is a working author and teacher, and there is an active worldwide network of “esoteric schools” organized by the Fellowship of Friends.

Websites maintained by former members and original reporting by the LA Times and others paint a very different picture of Burton and the scene at Apollo. For legal reasons it would be ill-advised for us to assert these conflicting opinions as a statement of fact, or to in any way confer judgement or cast labels upon the Fellowship, who are well within their rights as tax paying Americans to live together in a small, cloistered, religiously motivated group. There appears to be, even within true believers of the Fourth Way, significant disagreement over interpretation and implementation of practices—such issues are part of all religious traditions.

What we do know for sure is that they’ve got a lot of wine up there at Apollo; indeed, today’s modern revival of natural wine in America can trace its roots in part to the Fellowship, who have since the early 80s eked wine out of the land in Yuba County, in some of California’s truly wild, wild wine country.

***

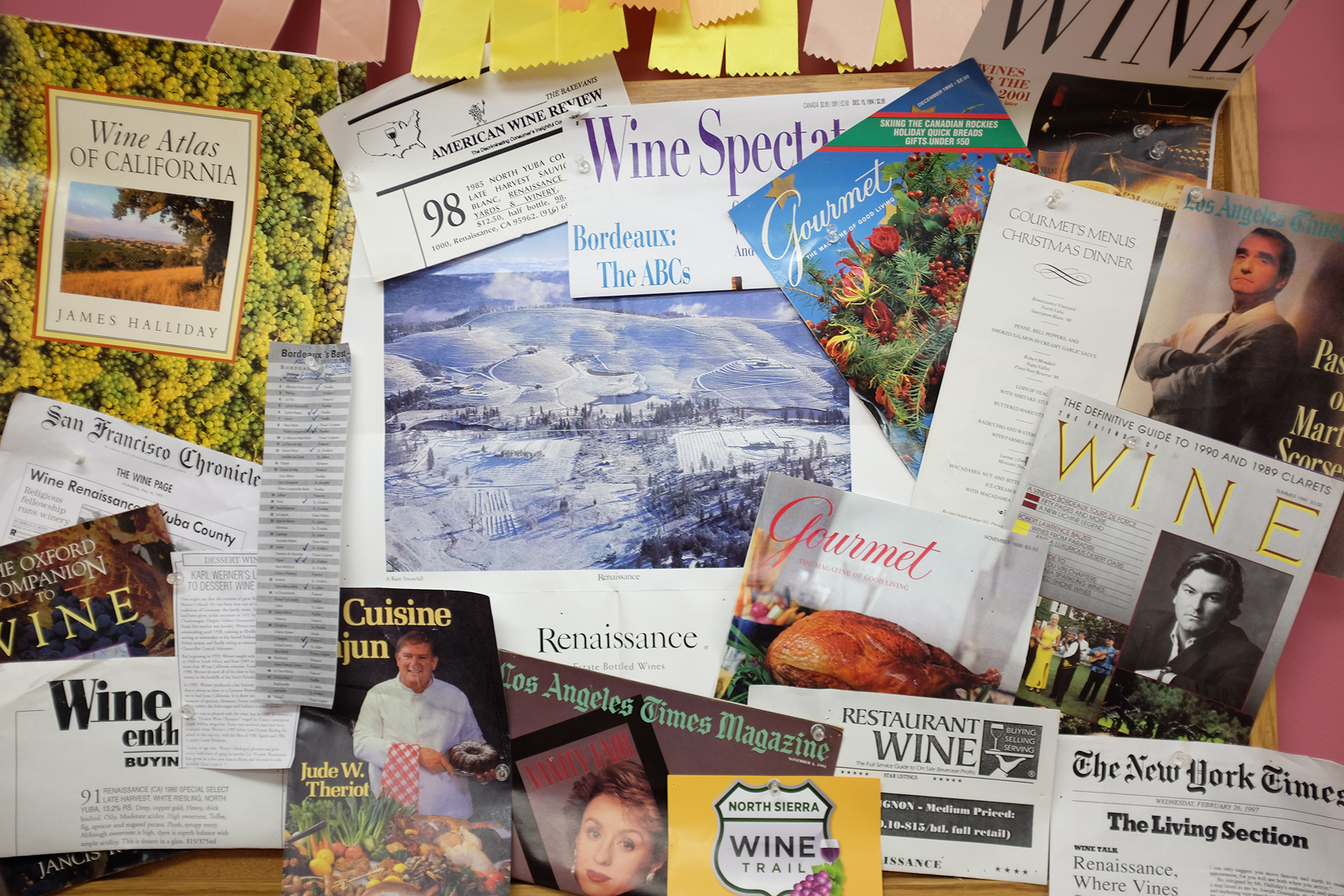

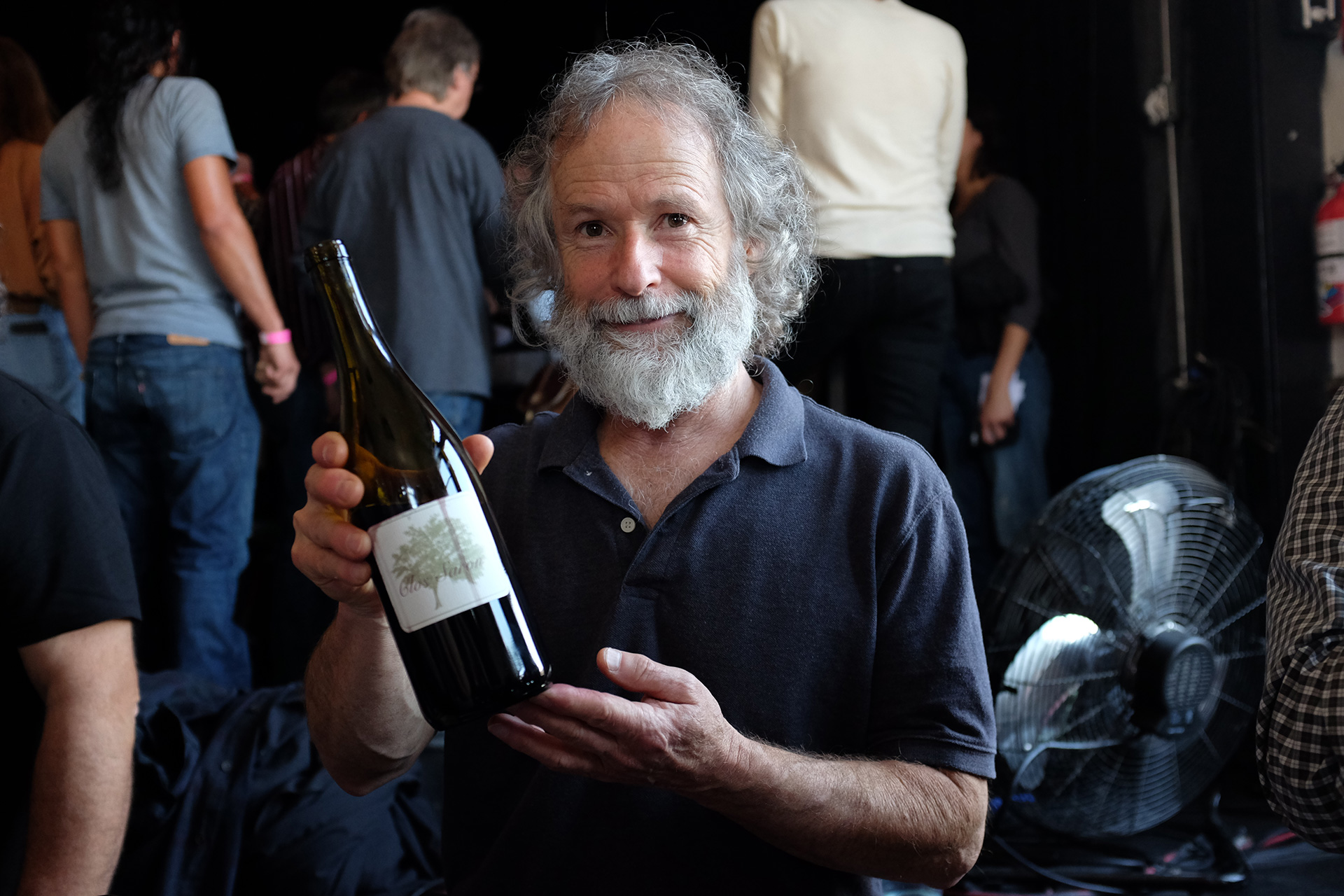

Besides being the geographical and spiritual center of The Fellowship of Friends, Apollo is the home of Renaissance winery. This is where one of his generation’s most iconic California natural winemakers, Gideon Beinstock of Clos Saron, got his start. No less an authority on natural wine than Alice Feiring has been covering Beinstock’s work since the mid-90s, when she wrote about Renaissance for, of all places, Elle Magazine. “He’s on the vanguard of natural wine in this country,” Feiring tells Sprudge. “For the longest time there was only Tony Coturri and Gideon. They have completely different approaches but are equally important in this country’s narrative.”

Beinstock learned about The Fellowship from a bookmark he found tucked into a philosophy book in the 70s, a practice The Fellowship still uses to intrigue new members. After Gideon learned about the group, he packed up and headed to California from France to become a part of the first days of The Fellowship. At that time Oregon House, CA was host to a rowdy and cerebral group of young artists, theorists, psychologists, and high-minded thinkers who were brought together by the promise of community and raised states of consciousness.

Today Apollo is an extravagantly decorated property with twisting roads lined with date palms and citrus trees and raised gilded statues at roundabout intersections. The most lavish part of the property includes meticulously landscaped areas with bronze statuary and fountains depicting legendary figures and guardian dogs. Adjacent to that are camels, an art gallery, and a rose garden. All these elements come together in a distinctly 20th-century hodgepodge of Neoclassical architecture, a visual encapsulation of what The Fellowship stands for and also the very particular filigreed taste of Burton.

The mantra and goal of The Fellowship is to “be present.” This means being present and deliberate in all things, including tasting. And more, the aim of the group is to raise oneself to a higher state of consciousness through that presence, great works of art, and hard manual labor (“voluntary suffering”). All these conditions come together to form a spiritual practice that just so happens to dovetail with the work and thoughtfulness that winemaking requires.

The winemaking facility, Renaissance, is comprised of a large cinder block winery, built by members of The Fellowship and tucked into the side of a large hill, designed to be gravity-run. In a previous iteration, the winery sported a giant inflated white containment bubble, like some urban tennis courts use as covering. Inside the plain-looking winery, the walls are covered with reproductions (by print or by paint) of famous works including “The Creation of Adam,” “The Starry Night,” and a portrait of Don Quijote. Most of the equipment is pushed to the side now—their last working vintage was in 2015—with a few barrels still lurking around the bunker-like building, as gold-painted cherubs hang from the ceiling. Behind a locked chain-link fence is a massive room used for storing boxes upon boxes of back vintages, more than a thousand in total, from splits to unwieldy 18 liter Melchior bottles dating back to the Reagan administration. It is a truly massive library, the result of an unusual combination of obscurity and moderately high-volume winemaking. There were years when Renaissance made as many as 40,000 cases.

***

The early history of Renaissance was full of good ideas that weren’t thought out all the way. From 1976-82, the vineyards were painstakingly terraced and 365 acres of vines were planted. Vines were own-rooted on low-nutrient decomposed granite topsoil, the very same kind of soil Beinstock farms at Clos Saron today. A winemaker named Karl Werner was the guiding hand behind the terracing and planting of the vineyards and was the group’s first winemaker. Prior to joining the Fellowship, Werner had worked at his family’s estate, Schloss Groenesteyn, in his homeland Germany, until they were rudely booted by the Nazis; later he helped establish Callaway Vineyards in Temecula and consulted for a retinue of mid-20th century California winemakers, including Mondavi. He was the winemaker at Renaissance until he died in 1988.

The wines during his tenure were heavily oaked and super bodacious California Cabernets, blends, and Rieslings. Werner’s widow, Diana Stefanini, was a student at UC Davis and did a lot of the mapping of the property before Werner arrived. She took over when he died for a few years until her last vintage as head winemaker in 1992. Under Stefanini, the wines of Renaissance begin to show more elegance and sense of place, with off-dry rieslings being especially good in her years. In 1993, Beinstock was put in charge and began making changes and defining the style of Renaissance towards something more recognizably natural—wines with, dare I say it, more presence.

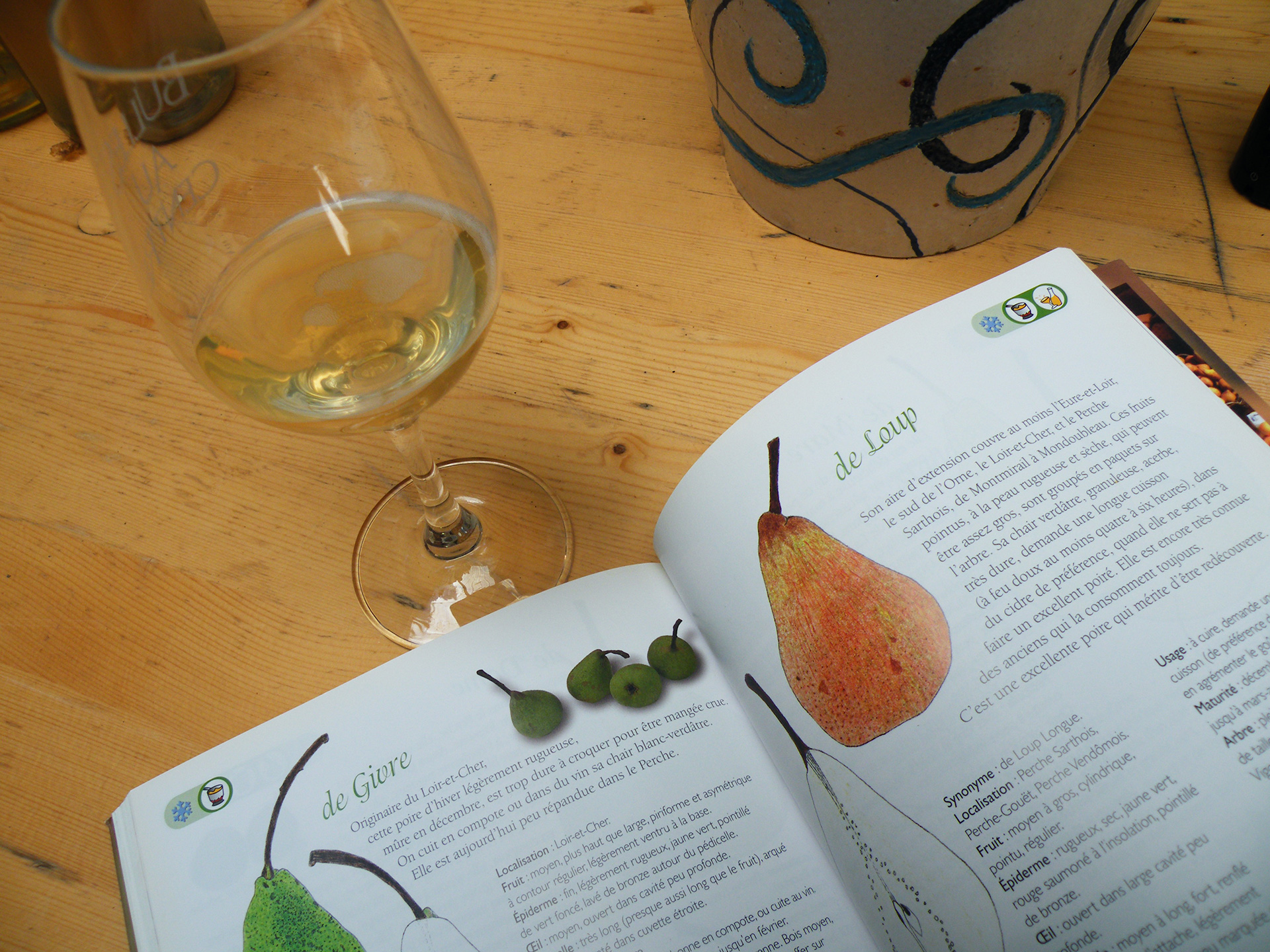

Beinstock had been working in the winery for a year or so by then, but before that had spent many years cultivating friendships and his own taste in wine by traveling throughout France. Though he was around for the planting of the vineyards back in the 70s, Beinstock spent most of the ensuing decades splitting time between Oregon House and France, and for a time in the late 80s was tasked with selling the Renaissance wines in Europe. He saw that at Renaissance, so much effort was being made in the vineyards, only to be covered up with oak, added yeasts, and other additions, as was the style at the time.

Beinstock remembers asking Stefanini which plots on the Renaissance property yielded the finest grapes. Her response was, word-for-word: “Our vineyards uniformly produce commercial quality grapes.” This was a disappointment for the budding winemaker, and so he began to make changes that focused exclusively on how to best express the site’s terroir. The first changes he made were to stop fining and filtering the wine. Then he stopped adding commercial yeasts, instead allowing the ambient Yuba County microflora to take its course. He also began lowering the amount of added sulfur, and in the following years, Renaissance switched over to using minimal oak. Back in the vineyard, a massive grafting program to eliminate less-suitable grapes was begun in 1994, in concert with a site-wide conversion to organic agriculture. From 1993-95, each of the dozens of dozens of sections of the vineyard were parceled out and made into separate wines so that they could understand better what they were dealing with, terroir-wise.

One of the most difficult and quirky elements of the vineyards is the terracing. When the vines were planted originally, terraces were cut into the ground without any consideration of the contours of the hills the vineyards were being established. Some vines would get radically different amounts of sunlight because of the impractical but beautiful installation of the terracing.

In 1998, after five years of running the winemaking operation at the Fellowship, Beinstock and his wife Saron Rice (for whom the winery Clos Saron is named) moved to the property they live on now, just down the road from the main gates of Apollo. Rice and Beinstock met at The Fellowship—he was making wine, she was working in the vineyards—and in 1999 they launched Clos Saron, continuing to divide labor together as husband and wife. “Being a cult member or whatever” Beinstock tells me—his words, not mine—“we didn’t have any money, and so we couldn’t really get a loan.” There were already some vines planted on the property, and a small hobbit-like winery facility capable of producing a barrel or so at a time, which had been built on the farm by another then-member of their Fellowship of Friends who was the previous owner. Start-up money came from “some farm administration”—a government grant of some sort (Beinstock wouldn’t share specifics)—and it required Clos Saron to operate as a business.

Up until that point, Beinstock’s experience in making had been exclusively at Renaissance. The winery was originally founded to be a way to bring in money for The Fellowship but in reality was always treated like a non-profit. Though they were selling wines, it was never reflective of how much wine was being made and had never been an effective money maker for the group, according to Beinstock. After Beinstock and Rice received the grant to fund their farm, they had to figure out a way to make money—a huge departure from his time with the Fellowship.

Beinstock was directly involved with making the wines at Renaissance until 2006, but won’t take credit for the wines from these years. In 2010 he and his family left The Fellowship, severing ties with Robert Earl Burton and cutting off Beinstock’s access to the fruit at Renaissance.

***

The wines from Beinstock’s time at Renaissance are elegant, revelatory even, and can go toe-to-toe with serious aged Bordeaux. Acidity, texture, and liveliness are their building blocks—you can taste the sense of place here, the spirituality and expressiveness of Beinstock’s work at Apollo. Today his Clos Saron wines are a continuation of the ideas and practices he was building at Renaissance, though perhaps with a different spiritual footprint.

From an outsider’s perspective, The Fellowship seems today to be in decline, compared to its 70s and 80s heyday. Numerous allegations have been made in and out of court against Burton, who is alleged to have made a habit of promising a higher state of consciousness to the young sons of Fellowship members in exchange for sex, according to the LA Times. The winery no longer operates, and Burton’s alleged doomsday visions—including an alleged prediction for nuclear war in 2006—have not panned out, thankfully. Because it’s such a personality-driven group and Burton is close to 80, it’s hard to know what will happen to the Fellowship, Apollo, all that art and sculpture, the Renaissance winery, and its massive stock of back vintages when Burton inevitably departs this earthly sphere for another form of presence.

But everything in wine is cyclical. The future of Renaissance may now be in the hands of a young couple, Aaron and Cara Mockrish, who operate a small winery nearby called Frenchtown Farms. They’re not a part of The Fellowship, but they are now leasing and farming some plots of older vines. The land at Apollo is special and they understand that. They’re even selling some of that fruit back to Gideon Beinstock, just down the road at Clos Saron.

Meanwhile, what’s left of the team at Renaissance is keen to sell off their old bottlings, which means there are deals aplenty for wine drinkers. You can pick up back vintage bottles of Renaissance at fantastically cheap prices, but the bottles can be variable, especially those oaky monsters from the Karl Werner years. Far better are his wife’s wines, beginning with the 1989 vintage, but it’s the wines from young Gideon Beinstock beginning in 1993 that should attract the most attention. At the moment, the winery is in the process of having many of their wines re-corked for stability, which is exciting for consumers.

These wines are special. They express not only the severe terroir of Yuba County, but something much more: an encapsulation of wine as a product of spiritual devotion, of the intertwining of religious truth seeking and winemaking. Here, the spiritual and the oenological combine in a way that feels similar to the Georgian monastery, or Nicolas Joly and his church of Biodynamics, but on Californian soils. An expression of the failures and excesses and glorious risks of a certain strange corner of the world at the apex of the 20th century. Wines of presence made all the more beautiful by their unusual backstory.

“These are the real cult California wines,” my host joked, and I laughed, but those are his words, not mine.

Jenny Eagleton is a freelance writer and wine professional based in the Bay Area. Read more Jenny Eagleton for Sprudge Wine.

*Ed. note: An earlier version of this story—as well as multiple features and books (from publications large and small) over the last two decades—incorrectly spelled Mr. Beinstock’s surname as “Bienstock”. We regret the error.