It may sound like baby-talk, but the French word glou-glou, semi-obscure for as long as anyone can remember, has now—for better or for worse—crossed over into international wine parlance.

It may sound like baby-talk, but the French word glou-glou, semi-obscure for as long as anyone can remember, has now—for better or for worse—crossed over into international wine parlance.

It has lent a name to wine bars in Paris and Amsterdam, to a wine tasting in New York, to a Baltimore wine import company, and most recently to a wine magazine in LA. Falling from the lips of Anglophone oenophiles worldwide, glou-glou is the most successful French linguistic export since ooh-la-la, a rarity in a linguistic era otherwise dominated by Anglophone neologisms like selfie and vape.

An onomatopoeic noun-turned-adjective imitative of both the sound of liquid leaving a bottleneck and of the rapid gulping of said liquid, glou-glou leads a small pack of recent French lexicographical imports driven by the surging global interest in French natural wine. (C.f. the phrases pét’-nat’ and vin de soif.) A glou is what Anglophones call a “glug”; a wine that is glou-glou is one that invites glugging. As such the phrase has found particular caché when applied to the bright, cool-carbonic-macerated natural red wines of the Beaujolais and the Loire valley.

It was in the Beaujolais that I first heard the phrase used unironically in casual conversation—not from a winemaker, but from a fellow harvester who had recently plunged headlong into the world of natural wine. “I love Beaujolais,” he enthused as we sat down to dinner in Fleurie. “It’s so fresh, so invigorating, so glou-glou.”

Yet the terms glou and glou-glou in France long predate the popularisation of natural wine. The earliest documented usage appears to be in Molière’s 1666 play The Doctor Despite Himself:

Qu’ils sont doux, bouteille jolie, Qu’ils sont doux, vos petits glouglous. How sweet they are, pretty bottle, How sweet they are, your little glouglous.

The word reappears in the work of Emile Zola and Alexandre Dumas, among presumably many others. Paris restaurateur Ludovic Dardenay, who founded his Marais natural wine bistrot Glou in 2008, directed me to glou’s most common French usage in the popular chanson paillard (drinking song) “Il Est Des Notres”:

Ami [nom de l’ami] lève ton verre

et surtout, ne le renverse pas

et porte le

du frontibus

au nasibus

au mentibus

au ventribus

au sexibus

à l’aquarium

et glou et glou et glou

Friend [name of the friend] raise your glass

And above all, don’t spill anything

and put it

from your forehead

to your nose

to your chin

to your belly

to your sex

to your mouth

and gulp and gulp and gulp

The word’s emigration into Anglophone wine circles is a more recent phenomenon.

“I first heard glou around 2003, when I started working with natural wine at Chambers Street Wines and began travelling to France with [late natural wine importer] Joe Dressner,” says sommelier Lee Campbell, who in 2015 organized a natural wine tasting in New York under the banner of “The Big Glou.”

“Glou meant fresh wines which didn’t fight the food for the spotlight,” she explains. “In NYC, we had just come out of a period when powerhouse, high-alcohol wines were in vogue: Cult-California, Priorat, etc. These glou wines were a revelation, a balm to my overtaxed palate.”

Joe Dressner’s son Jules, who nowadays runs the family’s eponymous wine import company, places his own introduction to glou-glou somewhat later. “The first time I heard the word was from [French natural wine importer] Guilhaume Gérard when I was working at [San Francisco natural wine bar] Terroir in 2010.”

In 2012, writing under the pseudonymous nom de plume “Eddie Wrinkerman” for his company’s website, Jules Dressner wrote an editorial entitled, “Drinking Like Fish: The Rise of Glou-Glou in Europe and Beyond.”

“More often than not, [glou-glou] wines tend to be lighter in alcohol, tannins (for reds) and body, but still have pronounced acidity, minerality and a real sense of terroir,” Dressner wrote.

Glou-glou reappears often in online writing by Dressner fils and his team, applied variously to wines from the Beaujolais, the Loire, Emilia-Romagna, and Sicily. But Dressner took care in his original editorial on the subject to include quotes from French Loire valley winemakers who credit the word’s application to natural wine to the circle of winemakers surrounding Marcel Lapierre in the Beaujolais.

Lapierre’s friend and fellow Villié-Morgon winemaker Guy Breton confirmed as much when I saw him in early November. Recalling the chanson paillard, I asked him whether glou-glou in French had always been applied to wine in an appreciative sense.

“No, that comes from us,” he said, indicating with a wave of his hand the surrounding village of Villié-Morgon, and his peers there. “The accent we put on fluidity.”

Aided by natural wine importers like Guilhaume Gerard and the Dressners, glou-glou has taken on a life of its own in English. The Portland Press Herald’s Joe Appel, writing in 2014, mistakenly pronounced glou-glou a “neologism, first uttered by someone in France at some point in the past five or so years.” (Dommage, Molière.) Bon Appetit writer Belle Cushing embraced the word’s less common usage as a noun in her 2016 article “The (Totally Fun, Not at All Stuffy) New Rules of Wine.” Her example sentence defining the term reads, “Some glouglou would really hit the spot. It’s my new beer.” (In the original French, the noun form usually refers to a sound, not the liquid making it.) The New York Times’ Eric Asimov, writing earlier this year, verbed the word: “[vins de soif] are relatively low in alcohol and high in acidity, so you can “glou-glou”…”

The English language, and American English in particular, is prized for its elastic qualities, so far be it from me to disavow new usages of glou-glou. One is nonetheless reminded of the Macarena dance craze of the mid-nineties, a heady moment when, for many politicians and commentators, it was unclear whether one could Macarena or whether one had to do the Macarena. If in Francophone wine circles the word glou-glou is almost normal, in their English counterparts it still retains a whiff of affectation from its recent-import status. A gentle backlash has been inevitable.

Says Lee Campbell, “Glou became a little exploited I think. And I’m guilty of being one of the exploiters. Because if the wine is affordable, approachable, and lower in alcohol, doesn’t that mean that we can drink tons of it, and whenever we want, wink-wink?”

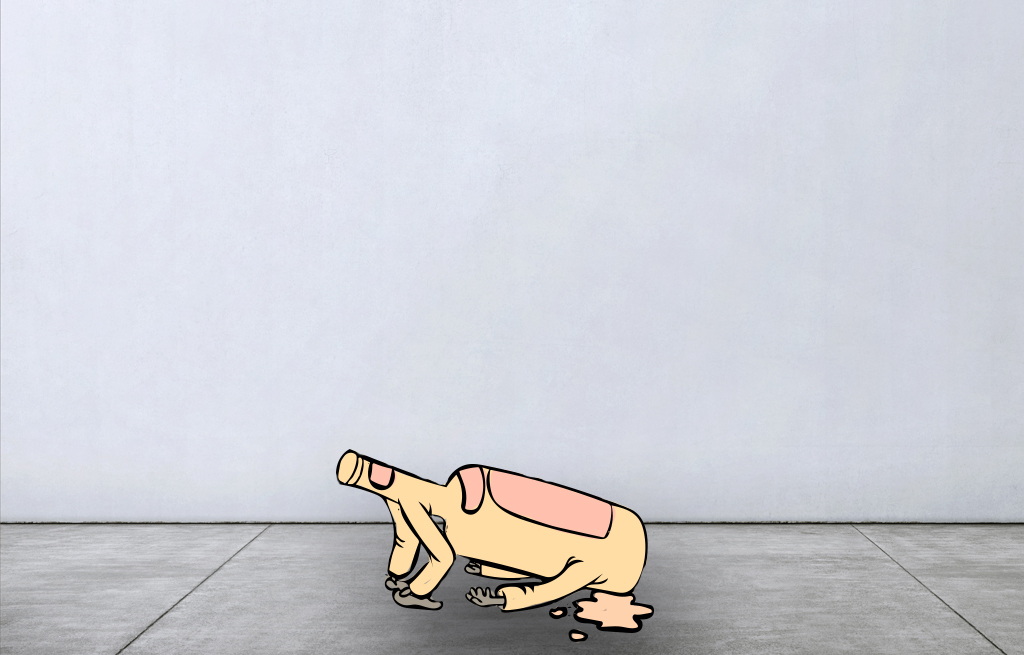

We Americans glug many things, after all; our average restaurant water glass qualifies as a swimming pool in France. But to glug wine is iconoclastic on both sides of the Atlantic, because glugging represents the opposite of la dégustation, the formal approach to wine tasting advocated by wine education guilds the world over. He who glugs wine is asserting a very different financial relationship to wine than he who takes great care to sniff and swirl and taste. La dégustation is for the bourgeoisie; glugging is for both the ouvriers who have worked up a true thirst, and the truly rich who have enough money not to care. A short examination of the pricing of natural wine in France versus the pricing of the same in the USA suggests that here in the USA we are probably using the word glou-glou in a slightly different way than our Francophone counterparts.

“But the soul of glou isn’t raging and gluttony and overconsumption,” Campbell clarifies. “It’s access, equality, health, and moderation.”

She alights here upon a more elusive notion embedded in the word glou-glou as it was popularized by Lapierre et al. The ideology of natural wine began as a reexamination of the means by which a wine is made. In resisting the addition of chemicals in vinification, natural winemaking aims to preserve not only the aesthetic integrity of a more ‘pure’ wine, but also its physical integrity—its “purity” itself. In this sense, a truly glou-glou wine is one that invites easy, copious drinking, and, crucially, doesn’t punish the drinker afterwards with a walloping chemical hangover. It is an expansion of the palate to encompass the drinker’s whole organism.

Philippe Quesnot, Grasse-based épiceur, veteran natural wine taster, and co-founder of the pun-heavy French natural wine website Glougueule, allows for this idea, if grudgingly.

“Perhaps in this limited circle of the small world of places where we drink natural wine, the expression has taken on a dimension to mean, ‘drink healthily?’ But really?”

For my part, I share Quesnot’s mild skepticism of glou-glou’s growing popularity as applied to wine. We have other words in English that mean roughly the same thing, from the hackneyed easy-drinking and drinkable to the more vivid and youthful crushable.

At best, glou-glou can be a useful way for retailers, writers, and sommeliers to introduce a novel wine ideal to clients too long accustomed to associating luxury with weight, tannicity, and persistence. At worst, glou-glou can be a useful word for retailers, writers, and sommeliers who wish to avoid speaking with any real precision about wine. If when describing Chambolle-Musigny we’re apt to break out the cadastral maps and Roget’s thesaurus, then I object to summarizing the wines of Chiroubles as merely glou-glou. The French have a more direct word for that, after all: jaja, any cheapo random wine without esteem.

Let us never confuse the glou-glou with the jaja.