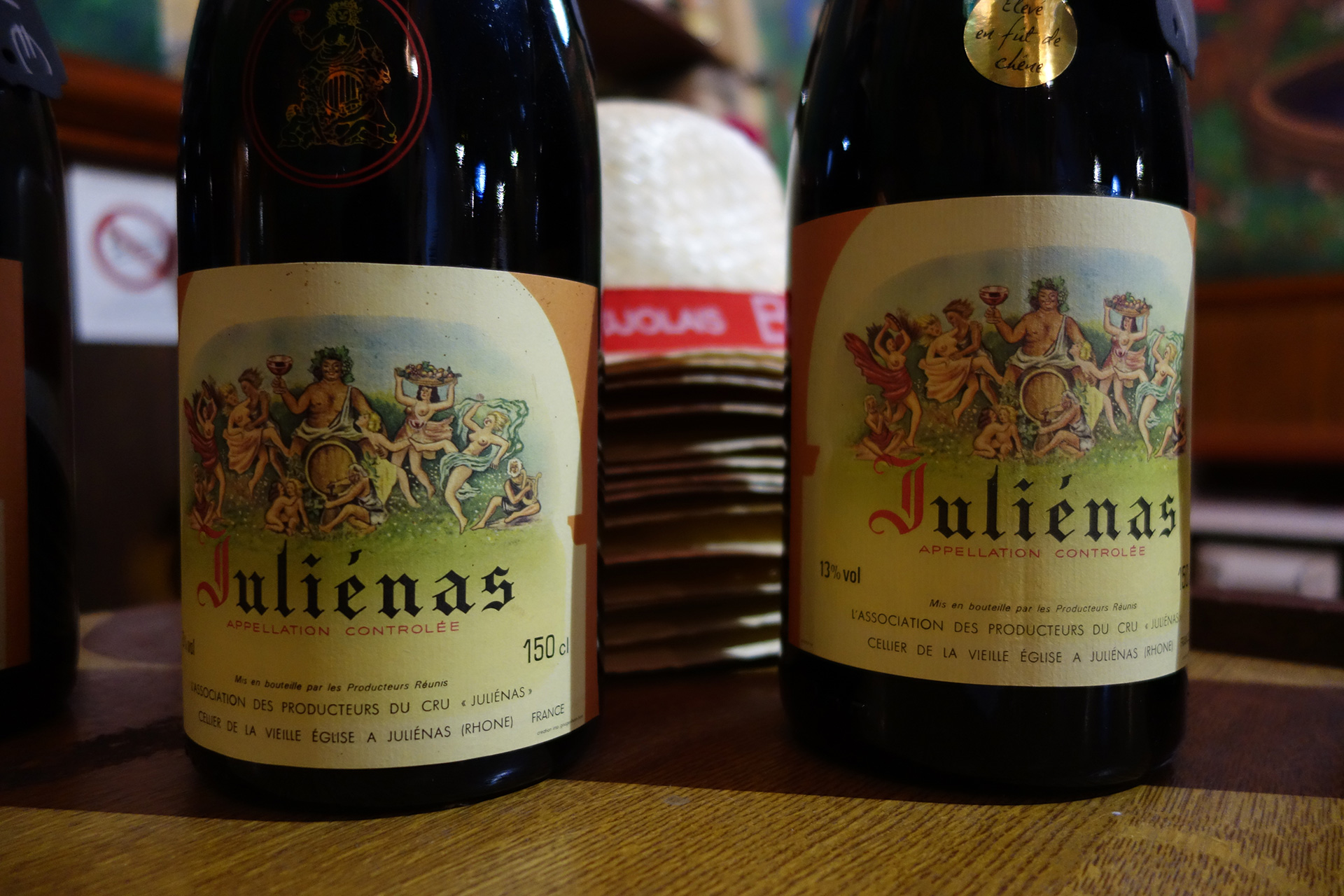

In the northerly Beaujolais cru town of Juliénas, the majority of wines produced in the appellation are sold in bulk to large négociant houses. But the 2016 vintage saw a panoply of ambitious natural winemakers try their hands at producing pure, quality-conscious Juliènas. The results begin to reveal what has for decades been lost—a picture of the cru’s storied hillside terroir.

A recurring refrain in my conversations with Beaujolais winemakers in recent years is the observation that a given cru zone has no Marcel Lapierre. Strictly speaking, no cru zone has a Marcel Lapierre, for the pioneering natural Morgon winemaker died in 2010. What these winemakers mean is that no winemaker of their cru has yet been responsible for launching its wine to cult status, as Lapierre was for his native cru of Morgon, and as one-time acolytes like Yvon Métras have become for neighboring Fleurie. The French term for such an estate is a “domaine phare,” a beacon domaine that leads the way for others.

The northerly cru of Juliènas—renowned for its high, steep slopes, rich in a magmatic schist known locally as “blue stone”—has no Marcel Lapierre. But since the 2016 vintage, Domaine Marcel Lapierre does have a Juliènas: the late winemaker’s successors, sibling winemakers Mathieu and Camille Lapierre, produced a Juliènas cuvée from purchased grapes that year. They vinified the wine in partnership with newly-installed Beaujolais winemaker David Chapel, a longtime family friend who has also released his own debut wine from the parcel.

In fact, the Lapierres are just the most high-profile of a panoply of talented natural winemakers who produced excellent Juliènas wines in 2016, ranging from Fleurie rising-star Yann Bertrand to Juliènas’ own Louis-Clément David-Beaupère. For drinkers seeking a new frontier of terroir-driven cru Beaujolais, it is as though a veil is being lifted from the cru, which for the past few decades has seen its historical esteem degraded by productivist agriculture, invasive vinification, and conservative bottling methods. These are, admittedly, the usual Beaujolais curses, rendered all the more lamentable in Juliènas by the soaring potential of the local terroir.

Domaine Lapierre and David Chapel purchase their Juliènas fruit from a south-facing parcel on the Côte de Bessay, a swelling, stony hill due north from the village of Juliènas, separating its eponymous appellation from that of neighboring Saint-Amour. Like the Juliènas appellation as a whole, the Bessay lieu-dit is a geological patchwork, alternating between blue stone, scree, veins of granite, and, unusually, sandstone.

“You see, at least it’s not totally herbicided,” says Chapel, gesturing down the slope from where we’ve parked atop the Côte de Bessay.

There is a thick grass band amid the rows, extending halfway down the hill before stopping and resuming up several rows over. Weeds grow sparsely among the vines in the thin, rocky soil. Chapel explains that the relationship with the parcel’s owner is new, and it remains to be seen to what extent Chapel and the Lapierres will be able to convince him to adopt more organic viticultural practices.

From the vantage on the Bessay hillside, we can see the village of Juliènas and, further south, the wooded north face of the Col de Durbize, separating Juliènas and Chénas from Fleurie. To the east, the landscape flattens out as it approaches Saint-Amour, whereas to the west are a succession of steep slopes leading to the adjacent towns of Jullié and Vaux. In that direction lies the majority of the appellation’s prized “blue stone,” which soil also underpins Morgon’s famed “Côte du Py” and much of the Côte de Brouilly appellation.

“Here, the soil changes slightly, all the way down,” Chapel notes, pulling weeds as he walks. We descend halfway down the parcel before returning to the car, where his wife, the American sommelier Michelle Smith-Chapel, opens a bottle of the Chapels’ inaugural 2016 vintage. The wine is a glowy translucent scarlet, a hallmark of unfiltered Gamay vinified the Lapierre way: cool carbonic maceration without much pumping over or punching down.

Because natural vinification is, above all, a return to the additive-free winemaking that was common before the 1980s, it makes no sense to speak of who made the first natural Juliènas. But the Lapierre-style vinification feels new in Juliènas in 2017. It heralds the arrival of a lighter, juicier aesthetic, one of debatable typicity in Juliènas, where the wines, historically, have been celebrated for their relative power and tannicity.

Natural winemaker Rémi Dufaitre, based a 30-minutes drive south near the Brouilly cru, has had a few tries vinifying natural Juliènas. He released his first Juliènas back in 2014, from a pink-granite-soiled parcel of just under two hectares he farms in the village of Pruzilly, in the steep western slopes of the appellation. When I call him in August, he’s preparing to bottle his 2016 vintage.

“Because it’s a bit austere, a bit hard, we’re obliged to do a longer élevage to reveal the fruit,” he says in his characteristic semi-intelligible growl.

Fleurie winemaker Yann Bertrand, who produced his first cuvée of Juliènas in 2016, reports similar experiences with a similar vinification style—despite sourcing his grapes at the opposite end of the Juliènas appellation, in the flat, clayey vineyard of “En Rizière,” near the border with Saint-Amour.

“It’s above all the terrain that gives it much more structure than what we know on the deeper sands of Fleurie and Morgon,” he says.

In acknowledging the peculiar muscularity of Juliènas’ terroir, natural winemakers like Dufaitre, Lapierre, and Bertrand are in a rare point of agreement with the old-guard of qualitative conventional winemakers native to Juliènas, such as Michel Tête, Vincent Audras, and Pascal Granger. Granger, a bespectacled former mechanic, is the most unabashed proponent of heavy, extractive wines from Juliènas.

“We can make wines that are normally more powerful than the other crus,” he affirms.

Granger’s house style includes long, Burgundian-style fermentation on starter yeasts, with full de-stemming and pigeage.

“I like those toasty, buttery notes,” Granger adds, revealing a cheerfully anachronistic palate. “Juliènas, on the good terroir, it’s made for the wood.”

Even winemakers of wildly different tastes agree that Juliènas possesses a capacity for richness. The other thing uniting producers of Juliènas is almost none are farming with organic certification. The exception is a Juliènas vigneron with too many hyphens, Louis-Clément David-Beaupère, the thoughtful proprietor of the certified-organic Domaine David-Beaupère in the southeastern lieu-dit of “La Bottière.”

On the evening I visit in late July, the house where he vinifies is rented to a troop of opera singers, who as we taste are stationed in a semi-circle around a swimming pool in the middle distance, warbling a celestial version of “Let It Be.”

“I don’t have many points of reference because I’m not a son of a vigneron,” he says. “It was a series of chance meetings that brought me to natural wine.”

Ten years into his career as a winemaker, David-Beaupère is still refining his approach. In 2017, he refrigerated the harvest before vatting, aiming for cooler, less extractive fermentation. In this, he’s following the example of Jean-Louis Dutraive, Yann Bertrand, Remi Dufaitre, as well as, of course, Morgon’s Domaine Lapierre.

“But I never manage to make wines as immediate as Yann [Bertrand],” professes David-Beaupère. “Mine always need another year or two. And decanting is obligatory.”

In the meantime, in his 2016 young-vine “Les Trois Verres” Juliènas, he has succeeded in drawing out the sunnier, more fleet-footed side of the adjacent deep-clay terroir of “La Bottière.”

The opera singers by the pool have moved on to Simon & Garfunkel and the sun has begun to set over the western hills when a diminutive older lady joins us at the picnic table where we sit. It’s David-Beaupère’s grandmother, who asks me what I’m doing in the Beaujolais.

“I’m writing a book on its wines,” I reply.

“That’s good,” she says. “There are so many prejudices about the Beaujolais. It experienced a sort of devaluation, we don’t know why.”

“Yes we do,” David-Beaupère interjects.

“Because vignerons didn’t work the way that should have,” says his grandmother solemnly.

“No,” counters her grandson, shaking his head and refilling our glasses. “It’s that we didn’t highlight the vignerons who worked well.”

Remi & Laurence Dufaitre – Juliènas 2016 (Jenny & François Imports)

Domaine David-Beaupère – Juliènas “Les Trois Verres” 2016 (Sacred Thirst Selections)

Domaine David Chapel – Juliènas 2016 (Grand Cru Selections)

Les Bertrand – Juliènas 2016 (Paris Wine Company)

Domaine Lapierre – Juliènas 2016 (Kermit Lynch Wine Merchant)

Aaron Ayscough (@a_ayscough) is the author of the wine blog Not Drinking Poison In Paris. His writing about wine and restaurants has appeared in The Financial Times, The New York Times: T Magazine, and Fantastic Man. Read more Aaron Ayscough on Sprudge Wine.

Photos courtesy of the author.